A Comprehensive Canvas For Designing Economies and Web3 Tokenomics

As a recognized authority in Gamification Design, I have spent quite a bit of time dabbling in designing virtual economies.

My leveling-up journey, which includes authoring the book “Actionable Gamification – Beyond Points, Badges, and Leaderboards,” (once stated as one of the top two must-read books in Web 3), has led me to develop the Economy Design Framework, which also heavily utilized in the tokenomics design space.

This framework was born out of a necessity when working with many companies. Many of my clients, despite their enthusiasm and vision, struggled with the fundamental aspect of creating a well-balanced economy. They would randomly decide between 5 points or 500 points for certain actions. But we know, in a real economy, just a 3% change in the interest rate would massively affect the behavior of all the banks, insurance companies, and all the consumers. There is a certain precision we need to care about when designing economies.

I also spent some time as the Contracting Chief Experience Officer of Decentral, working alongside Ethereum Co-founder Anthony Di Iorio, and helping numerous Web3 companies design their tokenomics. This has equipped me with unique insights into both short-term utility and long-term sustainability of digital economies. Further, my creation of Metablox.co, a Web3 blockchain museum, allowed me to explore further how to balance economies that are about timeless memories that would still matter three generations later.

The Economy Design Framework encapsulates these experiences and insights. It is designed to guide organizations through the complexities of designing balanced economies, integrating reward schedules, activity loops, progression curves, and optimizing the probabilities of mystery boxes and Easter Eggs.

Even though I see the greatest need of my Economy/Tokenomics Design Framework in the booming Web3 world, the framework particularly is valid for any type of ecosystem that involves rewarded behaviors and trading. It even applies to the real-world economy and can be integrated into my NationCraft Framework for governmental policy optimization.

Whether you are designing a gamified app, a decentralized platform, or a blockchain-based experience, the Economy Design Framework is your essential companion in navigating the intricate world of digital economics.

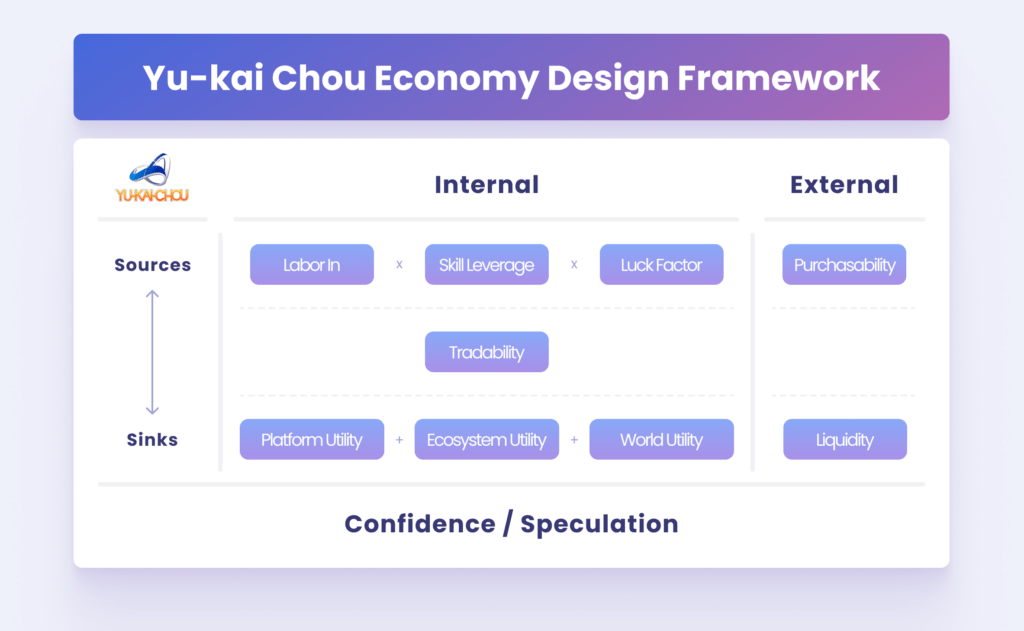

Components of the Economy/Tokenomics Design Framework

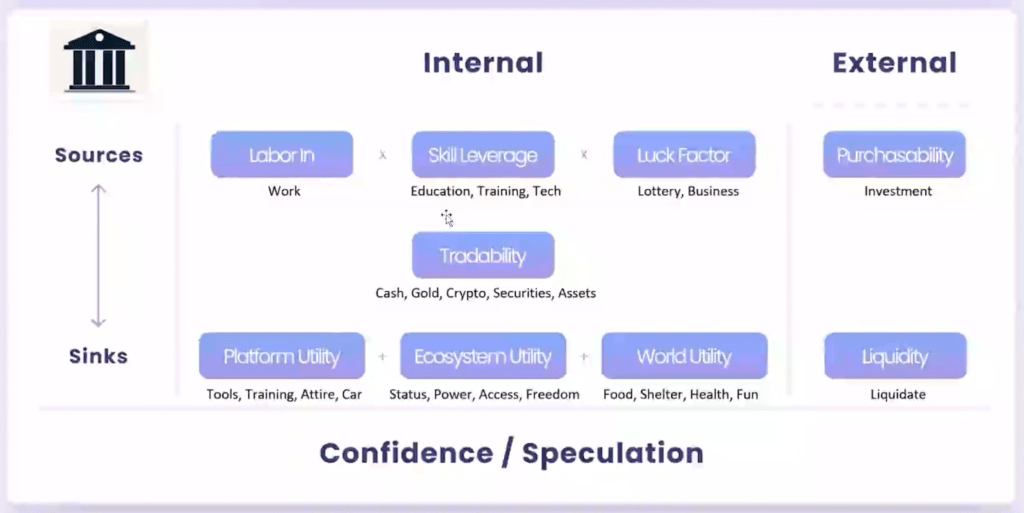

The Economy Design Framework is divided into a few major sections. There are the Sources, where value is created or stored in the economy. There are also the Sinks, where the value is expensed as utility or liquidity to the player, effectively removing the intermediate store of value (currency).

There are internal components, which are value created and dispensed within the economy system, and external components, which usually means other stores of value – cash/fiat or mainstream currency – get injected or withdrawn from the ecosystem.

Below the whole equation is Confidence/Speculation, which represents how much psychological hype is behind the ecosystem, artificially ramping up the perceived value of everything within it.

So let’s start off with examining the Sources, which follow the equation:

Value = Labor In x Skill Leverage x Luck Factor.

The Genesis of Value: Labor In

The fundamental level of where Value is created is how much purposeful Labor people put into a system. This notion of Labor is deeply rooted in the teachings of Adam Smith, the father of economics (I happen to have a degree in Economics from UCLA and am a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts in London, alongside Adam Smith).

It doesn’t matter what the labor is towards, as long as people consider it productive. If I play a game and spend 1000 hours “laboring” by killing monsters, planting virtual plants, or collecting stones, my reward for doing all of that is worth 1000 hours worth of labor. If you also want the same results or rewards but don’t want to spend 1000 of your hours to obtain it, you give me money or other storages of value, in exchange for my earned rewards.

This corresponds with Core Drive 2: Development & Accomplishment and Core Drive 4: Ownership & Possession in the Octalysis Framework.

The Booster of Labor in an Economy: Skill Leverage

The second Source of value creation within an economy, which serves as a modifier to the base Labor In variable, is Skill Leverage. Skill Leverage, or the ability to derive more value from an hour of labor through specialized skills, talents, or equipment, highlights the varied worth of labor across different sectors.

This disparity is why, in the real world, a doctor’s hour of labor is worth more than a janitor’s. The doctor possesses greater productive Skill that the janitor does not have. However, the Doctor still needs to pour in over a decade of intense labor to acquire his medical Skill Leverage and secure his degree.

Within games or virtual economies, strategic skill or sheer talent can amplify the value generated by a player. Some people have higher skills within a game, and some have certain gear that gives them power-ups that provide more value per hour of labor. Generally, increasing one’s Skill Leverage is the most reliable way to get an edge in life. This is why people spend so much time and money going to school, getting trained, and signing up to additional courses online from top experts.

Skill Leverage corresponds to Core Drive 2: Development & Accomplishment as well as Core Drive 3: Empowerment of Creativity & Feedback in the Octalysis Framework.

The Wild Card in an Economy: Luck Factor

The Luck Factor introduces an unpredictable yet fascinating variable into the equation. Whether it’s stumbling upon a rare item in a game or being at the right place at the right time in the business world, luck can dramatically alter one’s economic trajectory.

If you were playing a game, and due to extreme luck, found a powerful sword that, on average, requires a player 1000 hours of gameplay to find. Even though you just spent one hour of Labor, the sword is still worth 1000 hours of labor – something we call “expected value” in things that involve probability. So if I wanted the same sword but didn’t want to spend an average of 1000 hours, I still have to pay you 1000 hours worth of labor to get the sword from you.

The Luck Factor is why some people are disproportionally richer than others. Some people win the lottery, while others start a business that has perfect timing to meet the needs of a billion customers. Their “reward” cannot be calculated in how much Labor x Skill they put in, but more as an outlier wildcard in the Luck Factor. As you know, most people who buy lottery tickets just waste their money, and the majority of people who start businesses fail and even go into detrimental debt. The luck factor works both ways, and there is no need to be outraged by the ones that happened to be lucky.

Some economies have more mechanisms regarding luck and probability, which means there is more thrill and excitement, but also more risk and loss involved. This just depends on whether the userbase likes to be in a stable “work hard and grow” society, or the “Wild West” where you could achieve glory or die every day.

The luck factor corresponds greatly with Core Drive 7: Unpredictability & Curiosity in the Octalysis Framework.

This element of Randomness, coupled with Labor and Skill Leverage, paints a complex picture of how value is generated and perceived in an economy.

External: Purchasability

If players in an economy don’t want to labor to obtain goods or valuables, the aspect of Purchasability comes into play. Purchasability means that people can just buy resources in the economy. They put money in, and that’s how they contribute their value. They usually use fiat money like USD or highly-liquid fiat cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin or Ether to obtain valuable resources in a system.

In traditional mobile games, when people say, “Pay-to-Win,” it basically means that players can just spend “real money” to buy powers in the economy to gain an disproportional advantage over other players who simply put labor into the economy.

Of course, most mobile games don’t allow for “Liquidity” which means you can’t trade your valuables back to the central system. They take your cash and give you virtual items in their game economy, but there is no intention of returning that money back to you.

In the real world, it could mean that wealthy people could simply buy the best equipment, training, or business/advertisement to gain an advantage over others who work hard.

Player to Player: Tradability

Tradability within game economies refers to the ability of players to exchange items, currencies, or assets with one another. This feature can significantly enhance the gameplay experience by allowing players to trade for items they need or sell what they’ve earned for in-game currency or other valuable assets. However, designing tradability into a game’s economy requires careful consideration of its potential impacts:

- Economic Balance: Allowing players to trade items can affect the game’s economic balance. For instance, if high-level items are easily traded to new players (at near-zero costs), it can disrupt the intended progression and challenge of the game. Similarly, the ability to trade can lead to inflation if the supply of in-game currency grows unchecked, diminishing the value of in-game earnings and potentially harming player engagement.

- Player Experience: Tradability impacts the player experience by shaping how players interact with the game and each other. On one hand, it can add depth to the game, creating a social economy where players negotiate, barter, and build relationships. On the other, if not properly managed, it can lead to a disparity between players who can dedicate more time or real-world resources and those who cannot, potentially leading to feelings of unfairness or exclusion.

The decision to restrict tradability often aims to preserve the journey of skill acquisition and progression. It ensures that players experience the game as designed, from the initial learning curve to the satisfaction of achieving late-game milestones. By carefully designing these systems, game developers strive to create a balanced and engaging economy that rewards player investment and skill without leading to overabundance or devaluing player achievements.

Trading often involves Core Drive 5: Social Influence & Relatedness in the Octalysis Framework, and with limitations on trade, Core Drive 6: Scarcity & Impatience.

Sinks through Utility: Platform, Ecosystem, and World

In the evolving landscape of digital assets and blockchain technology, the concept of utility has become a cornerstone for understanding the value and application of various tokens and platforms. These utilities can be categorized into three distinct types, each serving different functions and catering to various needs within the digital ecosystem. Below, we explore these categories in detail, providing insights into their characteristics, applications, and significance.

By categorizing utilities into three distinct types, we gain a clearer understanding of the diverse roles and applications of digital assets within the digital economy and beyond. Each category showcases different facets of utility, from enhancing gameplay on a specific platform to enabling global, decentralized transactions, reflecting the broad potential of blockchain technology and digital assets.

1. Platform Utility

Platform utility refers to the specific functionalities or benefits that a digital asset offers within a particular platform or ecosystem. This type of utility is often confined to the boundaries of its native environment, where it can be used to enhance user experience or provide access to certain features. Examples include using Non-Fungible Token (NFT) characters to jump around in a game or stake cryptocurrencies on its own platform to earn returns. The value of these utilities is inherently tied to the platform itself, and their usefulness ceases if the platform becomes obsolete or loses relevance.

Most boosters, gear, and cosmetics in games are Platform Utilities. They make the game better, but have zero usefulness outside of the game. In the real world, tools that only help you within a certain work environment also don’t help benefit activities in other areas. The appeal of platform utilities lies in their ability to enhance the user experience and provide value within a confined dimension.

2. Ecosystem Utility

Ecosystem Utility extends beyond a single platform, supporting a broader network of applications and services. A prime example is Ethereum’s smart contract technology, which underpins a vast array of decentralized applications (dApps). If Ethereum were to disappear, numerous platforms that rely on its technology would completely collapse. Ecosystem Utilities are crucial for the smooth functioning and development of the broader digital environment, making them invaluable for the sustainability and growth of interconnected platforms.

Other solution platforms, such as IPFS, enable multiple platforms within an ecosystem to leverage their utility for storing files on the blockchain. In the real world, when a country issues a passport, it creates utility for the entire ecosystem of countries that accept the passport. However, not all platforms are required to recognize the Ecosystem Utility of a passport; for instance, Kazakhstan does not recognize Taiwanese passports due to its close relationship with China, which seeks to diminish the utility of Taiwan’s passport.

Ecosystem Utilities foster interconnectivity and facilitate a multitude of digital experiences across various platforms

3. World Utility

World Utility refers to digital assets that offer real-world applications and benefits beyond ecosystem activities, extending their impact into everyday life. These utilities address universal needs and behaviors, such as the desire to send money to others in a faster more secure way, attend exclusive real-world events, or connect to pundits that people admire. By bridging the digital and physical worlds, World Utilities showcase the transformative potential of digital assets and blockchain technology in reshaping everyday interactions and experiences.

For example, in the move-to-earn industry, people already have a desire to exercise more and become healthier (a “World Utility”). Even if the market declines and people lose their $500 “investment” in the ecosystem, they would still typically pay a personal trainer to motivate them to exercise, so they don’t feel their valuables are completed wasted. In this context, liquidity is less critical compared to the intrinsic value of the World Utility of exercising.

World Utilities represent the most expansive category, offering tangible benefits and applications in the real world.

External: Liquidity

Liquidity in the context of gaming and cryptocurrency is essentially the ability to convert tokens into fiat currency or other forms of tangible assets. Many games enable players to purchase in-game assets like gems but often do not support converting these assets back into real money, limiting their liquidity. While some games offer or restrict this feature, players sometimes resort to unauthorized channels, such as eBay’s black market, to sell their in-game items for real money, highlighting the existence of a demand for liquidity.

NFTs are often “in-game” assets that could technically be liquidated via marketplaces such as OpenSea or Spaace. Of course, just because it technically could be liquidated doesn’t mean it would be liquidated at a high value. That is subject to supply/demand, which is related to Utility and Speculation.

Confidence / Speculation

Everything described above is then leveraged upon by the Confidence and Speculation within the market. Assets might have an inherent utility value – via Platform, Ecosystem, and World Utilities – but their market value often reflects speculative confidence rather than just utility. In both good and bad market conditions, the perceived value of these assets fluctuates significantly, influenced by the collective confidence in their future worth rather than their current utility.

This speculation-driven valuation parallels the traditional stock market, where a company’s stock price can vastly exceed its earnings-based valuation due to speculative beliefs about its future dominance. However, market corrections can realign prices with more tangible utility values, demonstrating the cyclical nature of speculative investment and the enduring value of foundational technologies and utilities. When a market crashes, the price of certain assets and valuable fall to their basic Utility values (“How much would I pay to interact with my favorite celebrity” vs “If I put $100K into this I can probably get $200K back.”)

In essence, the market value and prices in digital and crypto economies encapsulates the complex interplay between player input, immediate financial convertibility, speculative confidence, and the intrinsic utility of digital assets. The market’s perception of these factors collectively determines the liquidity and value of digital tokens, influencing investment decisions and the broader acceptance and use of cryptocurrencies and in-game assets.

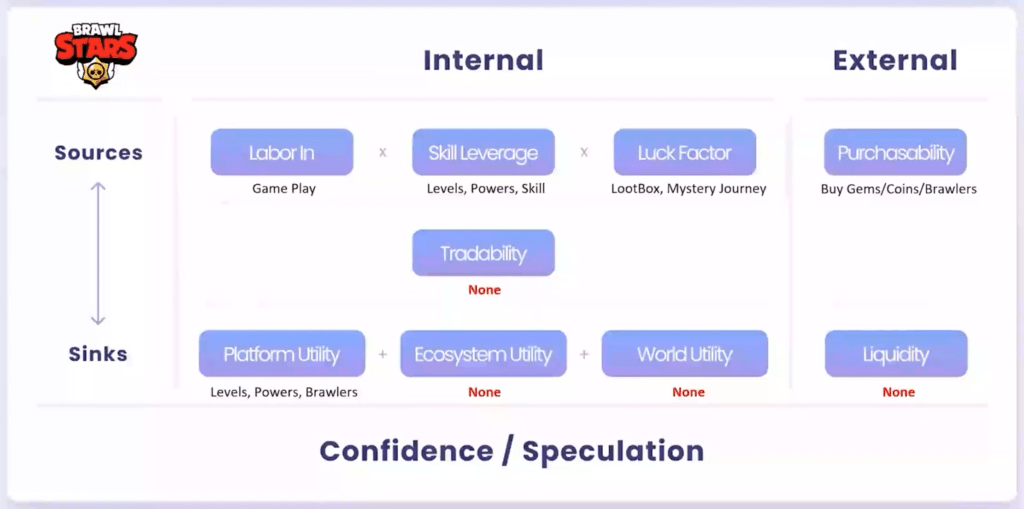

Example Economy Analysis #1: Brawl Stars

Let’s cover a variety of examples, from games to NFTs, to real world economies. The first is the mobile game Brawl Stars. It embodies the same concepts: labor time, skill leverage, and luck. In the game, playing constitutes labor—you need to log in daily, complete the daily quests, and you’ll accumulate coins, tokens, and various resources.

Skill leverage comes into play with levels and power-ups, allowing your characters, or brawlers, to level up and gain special abilities. This enhances your chances of winning and, consequently, allows you to gather resources more efficiently. Player skill is also crucial; if you’re more experienced or even an eSports champion, you can win your games more swiftly and amass a significant amount of resources within an hour. Then, there’s the luck factor, which is critical to consider for any project. How significant is luck in this formula?

In some instances, like in a casino, luck is nearly everything—you need to perform the labor of sitting there, inserting coins, and pulling the lever. Although some believe there’s a strategy in how fast or slow, or whether the machine is hot or cold, ultimately, luck dominates the outcome. There are games where acquiring the most powerful unit or a basic one is purely down to luck, rendering labor and skill almost moot. Typically, a game will incorporate a significant luck factor in their monetization strategies, forcing players to spend continuous money to “be lucky” and thus guarantee value.

Brawl Stars introduces loot boxes as mystery journeys, a concept increasingly regulated. In the Netherlands, for example, loot boxes are banned due to their resemblance to gambling. This has led to a shift from mystery box designs to fixed outcome designs, ensuring players know what they’re getting for their money or effort, thus avoiding the pitfalls of gambling psychology. This shift aims to make the outcome predictable. If you’re spending money or resources, you should know what you’ll receive in return. Consequently, many people also complain that this reduces fun and excitement in the experience, as Core Drive 7: Unpredictability & Curiosity (within the Octalysis Framework) is a Right Brain (Intrinsic) Black Hat Core Drive, which means that even though we feel out of control, our brains enjoy the experience.

In advising clients, I discuss strategies to navigate or even future-proof against lottery or mystery box compliance controversies. One approach is to offer something akin to exchange credits, ensuring actions always yield a known reward. This system still incorporates randomness in what rewards are available for purchase with the credits, but because actions guarantee some form of credit, it doesn’t feel like gambling.

Many games like Brawl Stars allow you to buy tokens or gems as their primary revenue model. This approach sustains the team of engineers, designers, and artists behind the game. However, these games typically don’t offer liquidity; you can’t sell these in-game resources for real money. This model ensures that if players desire specific in-game items or characters, they transact directly with the company, not other players, ensuring cash flow remains with the company.

This general game model primarily offers Platform Utility (Type I), where expenditures enhance the in-game experience without providing external or Ecosystem Utility (Type II). Once the game is deleted, all associated value is lost. Some utilities, like credit card points or airline miles, offer broader ecosystem utility, usable across various companies and platforms within a social ecosystem. However, there’s no World Utility (Type III) in the sense it doesn’t affect anything in the real world unless you see “having fun” as the Real World Utility.

This pattern of purchasing in-game resources to become more powerful in a game is common, where Skill Leverage and Platform Utility overlap with each other, reinforcing the platform’s Game Loop, and encouraging continued play to enhance one’s efficiency or power within the game environment.

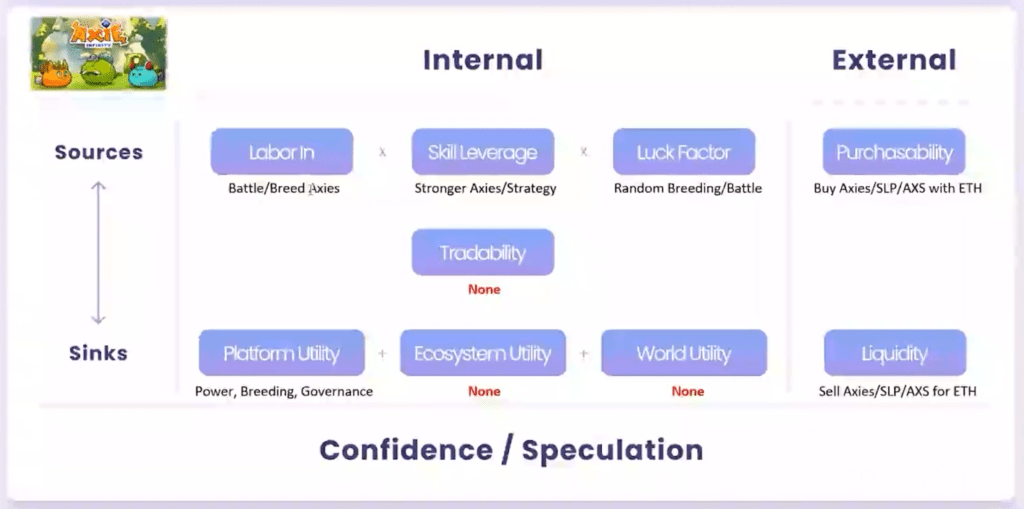

Example Economy Analysis #2: Axie Infinity

Axie Infinity is one of the pioneers of the “Play-To-Earn” movement, where by playing the game, people can make enough income that sometimes surpasses others with full-time jobs. This is because, compared to a traditional mobile game like Brawl Stars, Axie Infinity offers the Liquidity component, where people can trade in-game resources with near-fiat “real money” with others.

The game features “Axies,” which are small monsters that players collect. Additionally, there are two types of tokens: SLP (Small Love Potions), which enable you to breed your Axies, and AXS (Axie Infinity Shards), which serve as governance tokens, allowing players to vote on the platform’s evolution.

The value of governance tokens might not seem justifiable—for instance, spending $2,000 for a minimal say in the game’s development might not seem worth it for most people. This means that Platform Utility (Type I) is strong, but Ecosystem and World Utility are not that great. However, if there is an active marketplace for the in-game assets, it adds Liquidity, which drives up the value of the in-game assets.

In terms of Tradeability, you cannot buy another player’s Axies with SLP or AXS. Purchases must be made with Ethereum, which, similar to fiat currencies like the US dollar, contributes to Liquidity but not Tradeability.

The “Play-to-Earn” model of Axie Infinity means that while you’re playing the game, you can sell the resources you’ve accumulated on the open market for Ethereum. This contrasts with traditional gaming, where resources earned or purchased within the game usually have no real-world value.

However, the promise of Web3 includes a possibility of Ecosystem Utility (Type II) — where characters or assets from one game can be used or recognized in others, provided they share the same blockchain. They could potentially extend to World Utility (Type III) too, where having a high-level Axie might grant you access to real-world events or discounts, although this remains largely theoretical in the context of Axie Infinity.

The allure of Axie Infinity, particularly in countries like the Philippines, came from its potential for substantial earnings, with some players reportedly earning more than $3,000 a month, surpassing their parents’ income. This is because countries with better exchange rates like America value labor at a much higher price than the Philippines. An American could spend $10 to save 30-minutes of Labor, but to someone in the Philippines $10 might be worth three hours of Labor. Therefore, it was resource efficient for the Filipino player to play the game for hours and then selling the mined resources to the American player who didn’t want to grind as much.

This dynamic, for a time period, transformed the game into a viable full-time job. However, the reality is that for many people who joined later, the game’s profitability has not lived up to the liquidity value, with numerous players hoping just to break even on their investments.

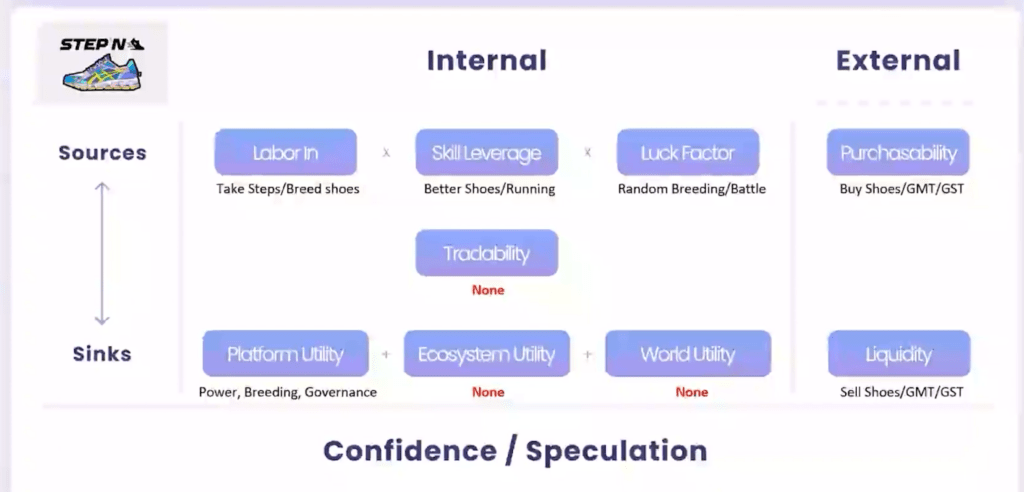

Example Economy Analysis #3: Step’N

Then we have something like Step’N, which pioneered the move-to-earn concept. It’s essentially an exercise app where you first have to spend a significant amount of money in Solana, another cryptocurrency, to purchase these virtual shoes on your phone. Each shoe has different characteristics; some are better suited for running, while others are for walking (which enables Core Drive 3: Empowerment of Creativity & Feedback in the Octalysis Framework). They detect your walking speed, and as you run or walk, you generate resources like GMT and GST. Since GMT and GST have an open market value, you can sell them, providing Liquidity to the Economy. In essence, this move-to-earn mechanism allows you to earn money as you exercise.

Many people wonder where the money comes from in move-to-earn. Step’N, the company, doesn’t directly pay you; rather, it creates GST or GMT out of thin air, and there’s a marketplace where other users will pay you near-fiat money for these tokens. This setup is fascinating, but one striking difference between Step’N and Axie Infinity is that Step’N offers World Utility (Type III) —exercise and fitness — which Axie Infinity lacks. I have a friend who, realizing he hadn’t completed his daily Step’N jog at 1 a.m., would get out of bed to jog for 20 minutes just to earn resources. When I was chatting with him at a conference, he even excused himself to run because his energy bar in Step’N had maxed out.

Even when the market is down, and GMT or GST’s value is low, users are still content because they’re getting healthier, which some argue is worth more than the money spent on the app. Thus, Step’N is arguably stickier than Axie Infinity because of this inherent real-world utility. Despite not being as “fun” or “exciting” as Axie Infinity and lacking certain game mechanics, Step’N offers tangible benefits in terms of health and fitness. So, even if the liquidity or profitability drops, users still receive genuine value from using the app through World Utility (Type III).

Addressing inflated prices and avoiding economic imbalances requires careful consideration of supply and demand within the game’s economy. Ensuring that hardcore players don’t reach the highest levels too quickly, while also providing average players with a sense of progression, is key to maintaining engagement without overwhelming or underwhelming the player base.

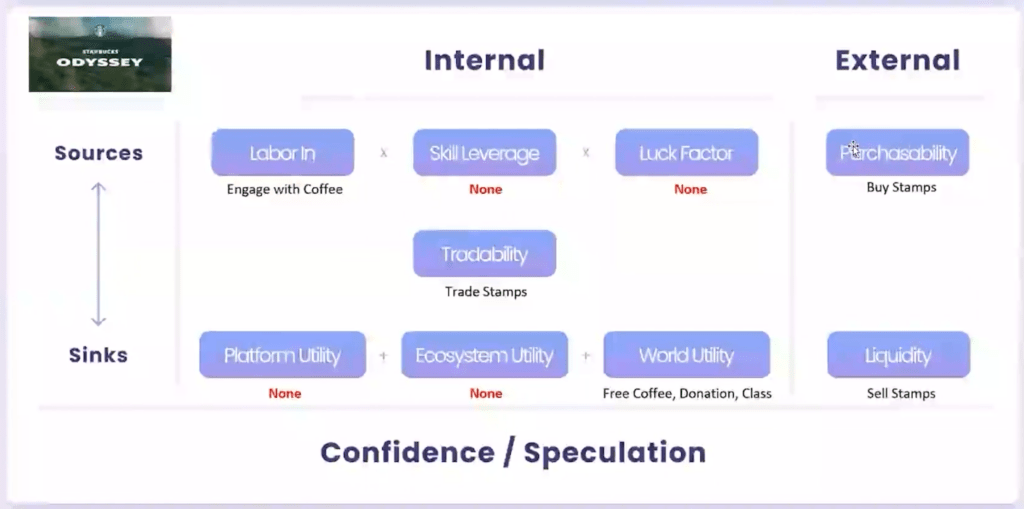

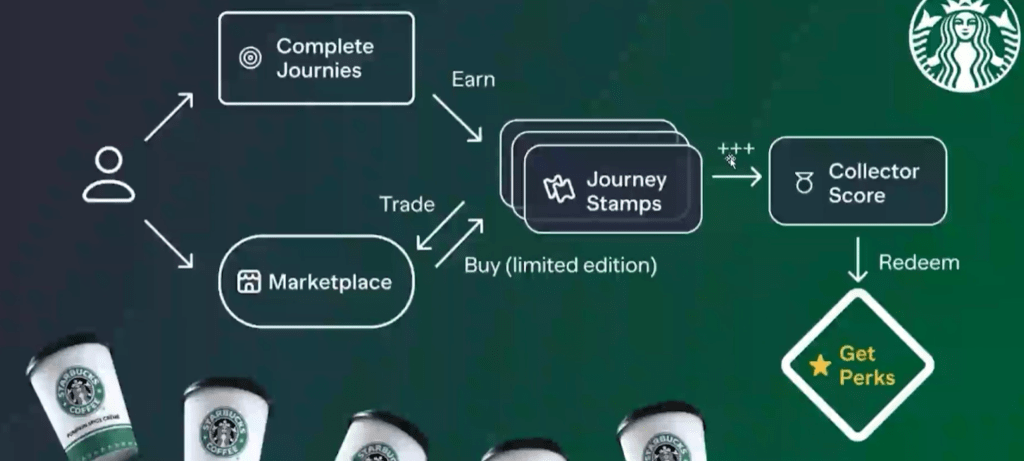

Example Economy Analysis #4: Starbucks Odessey

Starbucks Odyssey presents an intriguing concept, steering clear of directly using the term NFT, which I believe is a strategic move given the current sentiment toward digital assets. They’ve opted to term these as “journey stamps” and “digital assets,” adding a gamified layer to the coffee-drinking experience. While not fully accessible everywhere, the premise is straightforward: complete “journeys” by consuming a lot of coffee or learning about it, and earn journey stamps, which is Starbucks’ version of NFTs. These stamps are tradable, providing a means of Exchangeability within the game.

The engagement required involves “engaging with coffee” which is basically drinking lots of it, and that becomes the “Labor” input. The coffee itself isn’t the resource but rather the Stamps you collect by engaging with various activities, such as learning about coffee.

It appears you can directly purchase these stamps from Starbucks, and seemingly from other users, allowing for a more straightforward acquisition route beyond just engaging with coffee-related activities. As far as I can discern, there isn’t a Skill Leverage or Luck Factor incorporated into their system, making it a simple model that doesn’t rely on these typical gaming mechanics for user engagement or resource distribution.

Stamps could yield immediate benefits such as free coffee, donations towards fighting hunger, and educational classes about coffee. Starbucks positions Odyssey not as a game but as an enhanced loyalty program utilizing digital stamps and collectibles that resonate with the drink-to-earn model, encouraging users to engage in activities they likely already enjoy—drinking coffee—while offering additional rewards.

For improvements, one could consider how these journey stamps might evolve beyond mere images or icons. Is there potential for these stamps to offer Skill Leverage, similar to how Step’N operates, where certain actions or commitments over time could unlock unique benefits or efficiencies in earning rewards? This could add depth to the experience, making engagement more rewarding and dynamic for users deeply invested in the Starbucks ecosystem.

This concept of Skill Leverage could take various forms, perhaps rewarding users who drink coffee at specific frequencies with unique perks that accelerate benefit acquisition. Alternatively, long-term commitment rewards could incentivize consistent engagement over time, offering different benefits based on the user’s interaction pattern with the program.

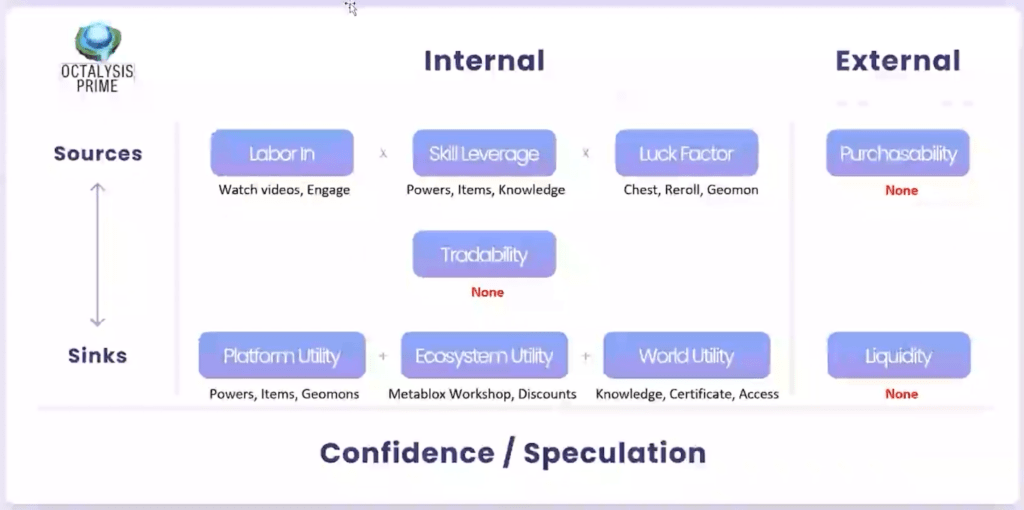

Example Economy Analysis #5: Octalysis Prime

Octalysis Prime is my own Gamified Education Platform, where I’ve made over 1200 videos (including on this Economy/Tokenomics Design Framework) It either operates on a freemium model that leads to a subscription.

Octalysis Prime’s ecosystem is focused more on engagement with content rather than monetization through user spending. The platform does not currently permit users to sell their “Geomons,” Chou Coins, or similar assets, creating a more contained ecosystem centered around content engagement. This approach was decided early on, preferring a model akin to a gym membership where users pay a monthly fee to access, learn, grow, and play as they wish, rather than pursuing a Pay-to-Win model that could potentially lead to users spending thousands.

The engagement (“Labor”) involves watching videos, taking on challenges with your gamification knowledge, and similar activities. The system includes Skill Leverage through various power-ups associated with different status levels and items that provide boosts. Knowledge is crucial; lacking it means your Geomons might escape from your collection. Luck plays a role but is considered relatively low in impact, besides being lucky and stumbling upon Legendary Geomons (only a 0.5% chance of getting it).

Tradability is not featured in Octalysis Prime; you can’t trade resources like Chou Coins or Geomons with other players. This decision was for balancing the experience economy. Allowing unrestricted trading could disrupt the journey, making the experience less rewarding.

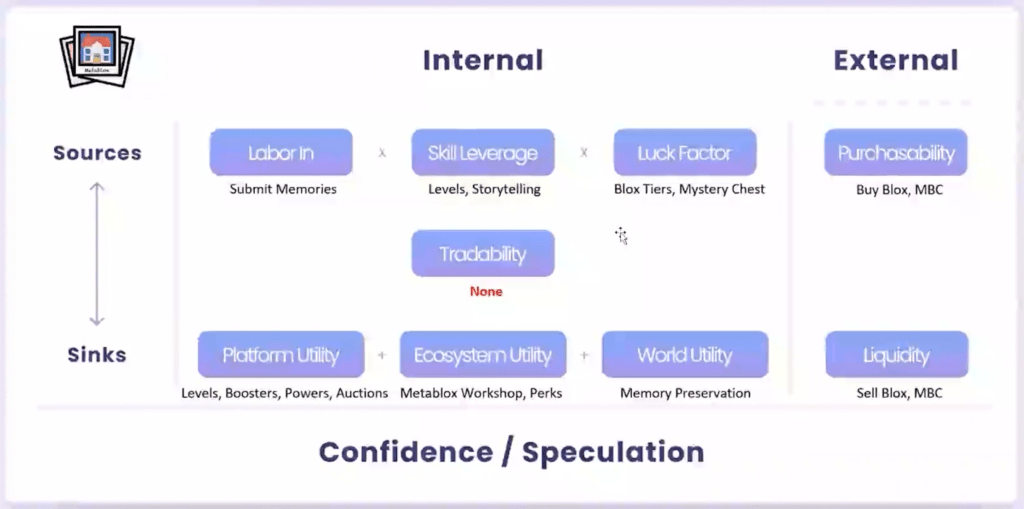

Example Economy Analysis #6: Metablox

Metablox.co is my Blockchain Museum project with the goal of preserving humanity’s most important memories onto the blockchain.

Metablox.co introduces a novel concept where users can submit memories to make their “Blox” more valuable. These blocks represent real-world land, and as memories are added, they level up, generating more Metablox Coins and MetaRent. This process requires Skill Leverage, as the quality of submitted memories can influence the Blox’s value. The Luck Factor is evident in the Tier System for Blox, affecting the amount of MetaRent received daily.

Metablox.co is exploring ways to enhance tradability and profitability, considering mechanisms like mystery chests that could offer free NFTs or additional Blox Credit for free NFTs. The focus is on increasing both Platform Utility and Ecosystem Utility, with efforts to collaborate with other Web3 projects to increase the value and utility of Metablox and its assets. The ultimate goal is to preserve important memories on the blockchain for humanity, akin to a digital museum, appealing to users who value the preservation of memories over the speculative aspects of the platform.

Example Economy Analysis #7: US Economy

To see if this Economy/Tokenomics is robust enough to fit into all scenarios, I took a stab at analyzing a real world real economy, specifically the US economy. The task proved somewhat abstract, particularly when considering Purchasibility and Liquidity.

Starting with the basics, Labor simply represents work—whatever job or tasks you’re engaged in. Skill leverage, then, is derived from education, training, and the technology you utilize; these elements act as boosters, enhancing your capability to perform work effectively. The Luck Factor can’t be ignored either. Some individuals might win the lottery, start a successful business, or land a significant job opportunity purely by chance, contributing to value creation within the economy.

Purchasibility, or the introduction of external funds into the economy (perhaps through exports) allows for the inflow of outside money in exchange for domestic goods or services. Another avenue for adding value without direct labor is through foreign investment, where money is injected into the economy to foster growth.

Tradeability in the economy is high, allowing for the exchange of various assets such as cash, gold, crypto, and securities. These transactions can be seen as trading in-game resources within the game economy.

Platform Utility are obtained with tools that facilitate participation in economic growth, including computers, cars, clothing, and training. These tools provide Skill Leverage, similar to how education equips individuals with knowledge and skills to perform better in the economy.

Ecosystem Utility can relate to how valuables in the US economy could gain benefits in multiple countries around the world. Status, power, access, and freedom represent elements that empower individuals in any economy. High status and access to resources can significantly enhance one’s ability to navigate and benefit from economic opportunities, both domestically and internationally.

World Utility could be intepretted fundamental needs independent of active participation in the economy. Essential requirements like food, shelter, health, fun, and safety are necessary even for those living off the grid or outside the conventional economic system. The existence of an economy simplifies access to these necessities, reducing the need for self-sufficiency in procuring basic needs.

Conclusion: Economy/Tokenomic Design Framework

In developing the Economy/Tokenomics Design Framework, I ventured to bridge the complex worlds of digital and traditional economies, drawing upon my extensive background in gamification, tokenomics, and ecosystem design. This endeavor resulted in a comprehensive guide that I believe is essential for anyone looking to craft economies that are engaging, balanced, and sustainable.

The framework reflects my experiences and insights, tailored to fit a wide range of applications from gamified platforms and decentralized blockchain experiences to influencing the macroeconomic policies of nations. It outlines how to manage the flow of value creation and consumption within any economic system, underpinned by the psychological dynamics of confidence and speculation.

By dissecting key components such as Labor, Skill Leverage, Luck, and the critical aspects of Tradability and Liquidity, I aimed to illuminate the multifaceted nature of economic interactions and their impacts on ecosystem vitality.

As we navigate the increasingly intertwined digital and real-world economic landscapes, the Economy/Tokenomics Design Framework serves as a foundational tool, offering clarity and direction amidst the complexity. It’s designed with a human-centric approach at its core, advocating for economic systems that prioritize meaningful engagement, innovation, and societal benefits.