Competitive gamification is certainly becoming a hot, new business theme in modern corporate development these days. It has been demonstrated to be effective in sales, where game mechanics based on competitive models are used to promote a “competitive interest” in engaging customers and closing deals. Now management is exploring other business functions which might benefit from competitive gamification mechanics and techniques.

But competition may not be effective, or even desirable in the enterprise setting. Why? Because it tends to create an unhealthy environment where employees put self interests above corporate and even customer interests. Instead of working towards a win for the company, a win for the customer, the individual just focuses on beating the internal competition – his colleagues and fellow employees. (To win the brass ring; that cash award or trip to Cancun.)

Gartner has predicted that 80% of the current enterprise initiatives in gamification will fail by 2014, primarily due to do poor design. Melissa Visintin further expands on this by stating that companies are trying to force game mechanics based on competition instead of understanding each situation and properly designing solutions based on the most appropriate mechanisms. It is not enough to simply throw together competitive game elements and expect the result to be effective.

What Exactly Is Gamified Competition?

A Working Definition of Competition

Mario Herger from Enterprise-Gamification.com explored the nature of competition from a number of perspectives. Drawing from Wikipedia, he has defined it in terms of ecology and sociology as:

“a contest between individuals and entities for territory, a niche, or a location of resources, for resources and goods, for prestige, recognition, awards, mates, or group or social status, for leadership.”

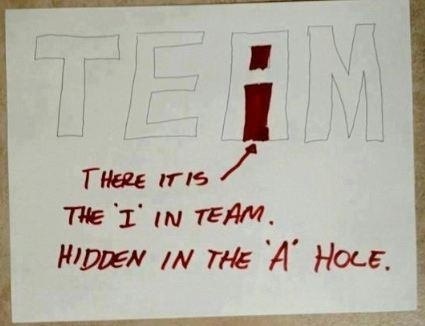

Notice the emphasis on the individual (or entity), and the need to “contend” or “contest” for something; implying that there will be a winner, as well as a loser. Maybe many losers.

In the enterprise this implies that we will have people competing with other people within the company. OK, that seems reasonable. But Mario Herger points out that this is contrary to the essential meaning of the corporation; yes, the very nature of an enterprise. For corporations are formed to bring people together and pool their different strengths in a collaborative setting. The fundamental design of an effective corporation taps the talents of its constituents to build something greater than the component parts. And yes, even more competitive in the external environment – the marketplace, where it faces the challenges brought forth by the other companies.

So now, do we want to introduce an anti-collaborative element – competition among the internal players, and potentially reduce their effectiveness as corporate team members? Possibly for customer engagement, but only after thoughtful analysis indicates that the benefits outweigh the risks, and possible long term detriment to the employees and ultimately the enterprise.

In general, adding the additional stress of competition to the challenges that employees face on a daily basis, will only result in a deteriorating situation with increased probability of burnout and uneven performance. Employees will become more motivated – to look for new opportunities elsewhere.

The Different Types of Competition

One perspective that we can view competition from is that of whether it can be deemed as healthy versus unhealthy. Mario Herger distinguishes between a “good” adaptive competitiveness and a “bad” maladaptive competitiveness by a set of specific characteristics.

Adaptive competitiveness has the following characteristics:

- Perseverance and determination to rise to the challenge, but bound by an abiding respect for the rules.

- The ability to feel genuine satisfaction at having put in a worthy effort, even if you lose.

- The fact that you don’t have to be best at everything, just in the domain you train for.

- Being able to deter or discourage gratification.

- Being marked by constant desire to strive for excellence, but not for the desperate concerns of rank.

Maladaptive competitiveness in contrast, is characterized by:

- Psychological insecurity and displaced urges.

- A person who cannot accept the losing part of competition.

- One who competes when others around are not competing.

- A person who has to be best at everything.

- One who doesn’t stop when the whistle blows.

- An individual who drags others into competition.

- One who will resort to cheating when he/she can’t win.

How Winners and Losers React

Now that we see that competition can be thought of in terms of adaptive and maladaptive forms, how do we view the players in these competitions? What are the common reactions that “players” have? Herger cites two Hungarian researchers – Martá Fülöp and Mihaly Berkics. They found that there are four common reactions for winners and losers.

Winners typically can either show:

- Joy, expressed through gleeful enthusiasm.

- Satisfaction with ones own competence.

- Denial of the win as way of social cautiousness. Those players would feel guilty and fearful of the losers’ reactions, like retaliation, so winners would mask their inner joy and not express it openly.

- Narcissistic self-enhancement, where the winners would feel a malicious superiority over the losers.

Losers typically can display:

- Balanced expression of sadness and disappointment, but with a graceful acceptance of the loss and a promise to be better the next time.

- Indifference, denial of loss, where they wouldn’t care; emotionally disinvested.

- Avoidance and self-devaluation, where the individual becomes their harshest critic. Often leading to extreme embarrassment, self-hatred, self-defined liability.

- Aggression towards the winner, overcomes by envy, anger and hatred of the winner.

- The researchers found that the most common winning reactions, were the first two – “joy” and “satisfaction”. Together they represented 75% of the reactions expressed by winners. In contrast, the most common reaction to losing was the first one: “sadness.”

A Little Neurophysiological Background

Another aspect of the competitive situation is that of human neurophysiology. Herger points out that there are underlining neurophysiological reasons on how well people deal with competition. He notes that some are hyper-competitive and thrive with competition, while others fail under stress scenarios, despite being very knowledgeable and skilled. These distinctive groups are the “Warriors” and the “Worriers”, respectively. Warriors see every challenge as an opportunity to gain something, while worriers fear lose and won’t take a risk.

Humans plan, evaluate potential future outcomes, differentiate competing thoughts, and attempt to resolve conflicts in the prefrontal cortex region of the brain. The neurotransmitter the provides the chemical stimulus to this region is Dopamine, the proverbial “reward” transmitter. However, too much dopamine will lead to an overactive state or “overload”.

To moderate and reduce excessive amounts of Dopamine the body produces the enzyme Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT). There are two types of this COMT that act at different rates – one faster, the other slower. Among Europeans, 50% of the populace have both forms of the enzyme, while 25% have only the fast form and 25% have only the slow form.

As a result, the 75% that have the fast COMT can cope very well with stress, while the 25% that don’t will overload faster. While the fast COMT individuals need stress to perform and tend to be good competitors, the slow COMT individuals overload and tend to not be good in competitions.

Alas, there is another factor that complicates the situation. Slow COMT subjects have been found to perform very well in a mastery situation. A mastery situation is where there has been previous, extensive training for a particular scenario, such as in the case of a flight simulator. An example would be the case for pilots who have gone through hundreds of simulations involving crisis scenarios. They then tend to outperform the “fast COMT” subjects. In contrast, for learning situations, where new knowledge is acquired or creative solutions are needed, the stress level is similar for everyone. Here the “fast COMT” individuals will perform the best, while the “slow COMT” individuals will falter.

Noted Gender Differences

An interesting aspect of competition is the difference in how men and women approach it. In Richard Bartle’s Player Type matrix we find that the most competitive group, the killers account for less than 5% of all players, if the classification is based only on their dominant trait. That is, only being classified as a killer, socializer, achiever, or explorer. Somewhat surprisingly, of this small percentage of the population, essentially zero are women.

This doesn’t imply that women don’t compete, but that they compete differently. They just enter competitions with different considerations. Mario Herger points out several gender difference between how men and women approach competition.

When men compete, the following are observed:

- Men compete, when there is any chance to win. Even a 10% chance.

- The highest achieving men in a group may make other, lower achieving men become depressed. They do not lift them up to higher achievements.

- Men work in groups.

When women compete, the following are observed:

- Women will compete when there is a high chance to win, because women are better judges of their own capabilities.

- The highest achieving women serve as “shining lights” for other women, they pull lower-achieving women up to new, higher levels of achievement.

- Women work in dyads, which discourage competition but emphasize relationship. Therefore, to enter a competition, women must have a very good reason to sacrifice a relationship. When forced to do, they really feel miserable.

- During a menstrual cycle women tend to overload faster, because of already high dopamine levels.

Some Cultural Differences

Mario also expands on the fact that different cultures also view competition differently. He points out that the typical “Employee of the Month” plaques that are so prevalent among the companies found in the US, would seem very odd, even strange in the more egalitarian societies found in such countries as the Netherlands, Germany, or Austria. Being an Austrian, he reveals that a company member receiving an “Employee of the Month” award would likely invite mockery and envy from others, so he wouldn’t want the exposure.

In another example of cultural differences influencing a competitive situation, Mario states that Russians would find these awards quite suspicious. They have had the “Hero of Socialist Labour”-title in the past. And now these awards have returned. But everyone knows that these people where not really the heros. They were just the hard line communists or party followers; people to avoid.

Asian cultures tend to prefer group harmony instead of promoting the individual. In general, competition would be counterproductive to the group harmony, eroding it’s strengths. A compromise might be to acknowledge the works and achievements of some groups, but not specify a winner(s). Essentially naming the highest ranked teams, but without specific winners.

When Competition Works

Mario feels in some cases that competition has the potential to work. What situations would be more likely for competitive design to succeed?

Here is a short list of when competition works:

- In mastery situations

- In gain-oriented situations and attitudes

- When the Individual Zone of Optimal Functioning (IZOF)

- When players care about the team

Competition does not work in:

- Learning situations

- Prevention-oriented situations and attitudes (unless when not performing means loosing points etc.)

- When teams are too harmonious

- When creativity is required

- When the competition is regarded as skewed

A well-designed game makes sure everyone is having fun, even in competition

In the corporate environment, motivation can be viewed as the process to engage employees and encourage them toward progress and achievement. To foster cooperation and collaboration, and in doing so, improve themselves and the company they work for.

Though game mechanics can be used to motivate employees and promote the behaviors that the company wants to see, each initiative should be well thought out and designed with the most effective elements. Arbitrary use of game elements modeled on competition may be useful for short term sales initiatives, but may be disruptive and anti-productive in the long term.

Instead of taking the zero-sum approach to try and motivate the best performers, we should consider strategies which bring individual strengths together to produce a more effective “corporate team”. That formula will always “out perform” the individualistic paradigm. It will help preserve and improve a positive corporate culture, support and encourage the development of talent and skills, and increase competitive strength where is really matters – outside, in the marketplace.

A gamification lesson from John Wooden, the man who knew his game

You may notice that the key characteristics of adaptive competition have much in common with the often quoted definition of success by John R. Wooden:

“Success is peace of mind which is a direct result of self-satisfaction in knowing you made the effort to become the best of which you are capable.”

A highly successful basketball coach, teacher, and corporate speaker, Coach Wooden was able to motivate many by focusing on self improvement, cooperation, and team concepts. Emphasizing that motivation is founded on a passion and love for the game, his teams were some of the most successful in the history of collegiate athletics.

(Thanks to Jerry Fuqua for helping me tremendously on this Post.)

16 responses to “Gamified Competition in The Enterprise Workplace”

Success = peace of mind – John Wooded. I never heart that before, but it resonates with me. Thanks.

Maybe gamification is also the key, specially in those jobs where people are too confortable and need motivation in order to improve

Excellent article!!

I am uruguayan, and soccer is the most played sport in my country. My countrymen are very likely to engage in all kind of competition but maybe for our deep connection with soccer competitions we enjoy far more those activities where there’s always a chance to compite again and it’s always a chance of winning.

On second thought It seems to me that this could be a must when designing in-work gaming competition as that way most of the undesirable effects of competition are removed

Stay awesome!

I am in doubts about ‘When creativity is required’, I thought it is necessary part of competition – show own creativity to gain goals

Should it not normally be that gamified competitions are based on that all can win? It is not me against you but rather us vs the game. If both do what is required we both win – and if none do it none of us win.

Also a note on team based competition – a common issue in e g sales teams is that some do more of the work that others which can cause problems within the team. So rules on individual performance need to be there as well.

That’s true – it’s like the classroom with one good student in a group and everyone else just copies her or write their names on the final deliverable.

Designing a good motivation system is often very delicate…

Group quests in WoW and other assignments in games where you have to cooperate to overcome a challenge. Actually lots of sales commission targets are group targets, that are aimed to foster group feelings.

“Creativity is does not work when creativity is required”

Please explain InnoCentive then 😉

http://www.innocentive.com/

Any examples of team-based competition where group members work to earn “points” toward a reward that all team members get? I’m not referring to “teams vs other teams, but a team that is competing with the game itself.

Love the article. A very important aspect of the competitive part of gamification to take into consideration when it comes to Enterprise Gamification.

Thanks for the feedback. Yes – those are great insights that any system designer must take in consideration 😉

MichelleAndreassenThanks for the feedback. Yes – those are great insights that any system designer must take in consideration

I was glad I read the article before my presentation at QCon New York, because I didn’t have that aspect in it, so thanks for that.

I see you’re going to be at the Gamification conference in Denmark tomorrow. Would have loved to go, but I pretty much drained my account in New York last week!

Hope you enjoy your stay here in Denmark!

MichelleAndreassen Sounds great! Look forward to meeting you some time 😉

Another great blog, thank you very much for sharing. I particularly liked the gender differences and those of culture. My last office in New Zealand had about 15 different ethnicities and within that very different types of people such as cartographers, developers, database specialists. You couldn’t get much more complexity from a gamification perspective. Yet they did enjoy games, particularly where everyone could win.

Luigi Cappel Thanks Luigi! There’s a lot of intricacies in designing a fun game environment. But some of the most popular games are global and cross-culture, which means there are possible solutions out there ready to be discovered!